When I began my MCAT studies, I took a risk when I refused to sign-up for a $3,000 MCAT Prep Course. In searching for a better solution, I did what I have always done in all of my college courses – make flashcards. When it came to learning the vast amount of information for the MCAT, I found that not just making flashcards, but making and using HIGH-QUALITY flashcards, would be the basis for my studying, and ultimately for my Free MCAT Prep Course. After years of “flashcarding”, here is everything I know about how to memorize anything with high-quality flashcards.

HOW IT ALL STARTED

When I was 16, I loved running. In fact, I loved it a little too much. After becoming the fastest runner in my high school as a Sophomore, I ended up injuring myself beyond the point of no return. I had run myself into the ground.

It was at this point in my life when I began reflecting on my priorities. I realized I had been spending way too much of my time seeking my own glory in sports and not enough time on the things that matter most: God, family, and yes, even schoolwork.

Seeking my own glory as a runner…

It was at this point that I became obsessed with the science of learning. I would go to the school library during lunch time and read books about the brain and how it stored information. Based on what I was learning, I started developing my own learning methods. Eventually, I developed a learning technique that transformed me from an average student into a straight-A college student.

My learning technique can be used to perfectly learn almost anything. And the best part is that this technique results in long-term retention. You will not forget what you learned.

AVOID INEFFECTIVE LEARNING TECHNIQUES

Now, before I share my approach with you, I first want to discuss learning techniques that do not work. They are very popular, but oftentimes popular methods are ineffective. Average techniques earn average results.

Rereading

Rereading is the least effective technique by far. As mentioned in the book Make it Stick, “Rereading has three strikes against it. It is time consuming. It doesn’t result in durable memory. And it often involves a kind of unwitting self-deception, as growing familiarity with the text comes to feel like mastery of the content.”1

As hinted at here, one of the major problems with rereading is that it results in what scientists call the illusion of competence.2 An illusion of competence is when you think you know something, but you really don’t.

When you reread material, you mistake recognizing the material for knowing the material. You think to yourself, “I’ve seen this before; therefore, I know it.” You may understand the material, but if you are asked to recall it on a test, you may struggle. This is why students will often feel ready for a test, and then flunk it. They are falling prey to the illusion of competence.

Taking Notes

Taking notes is by far the most popular learning strategy of college students, but there are two serious issues with it.

First of all, taking notes often takes the form of copying down exact phrases from a textbook or lecture. When you copy down information, you are not processing it, you are printing it. In one ear, out the other.

Second, and most importantly, reviewing notes is no different than rereading the textbook or rewatching a recorded lecture; thus, it will result in the illusion of competence: “growing familiarity with [your notes] comes to feel like mastery of the content.”1

Now, I get it. You like taking notes. It feels natural. The whole process of taking notes is glorified on Instagram by a whole new wave of fancypants #studygrammers. But look, no matter how you take notes, the problem remains. When it comes time to prepare for the test, the only option you have is to reread your notes, and rereading is proven to be the least effective study method bar none.3

Cute notes are still notes, one of the least effective study methods…

“But I got an A on my last test and all I did was re-read my notes right before the test,” you say. My response to this is, “but how much of it did you remember a week after your test?” My guess is not much. You see, oftentimes students can get by with just rereading notes, but when it comes time for a comprehensive final exam, these students will struggle big time.

If you want to truly succeed as a learner, you need a technique that will result in deep, long-term retention. When I was in college, my favorite week was finals week. While all my classmates were freaking out, attending boring review sessions, and spending sleepless nights rereading their notes, I was enjoying myself. I had already put in the work during the semester to cement the concepts into my long-term memory, resulting in my ability to easily destroy all my finals on just the first day or two of final’s week. Final’s week was easy as pie thanks to the learning technique I’m about to share with you.

RETRIEVAL PRACTICE IS THE MOST EFFECTIVE LEARNING TECHNIQUE

The basis for my learning technique is retrieval practice, which research proves to be the most effective learning method: “Today, we know from empirical research that practicing retrieval makes learning stick far better than reexposure to the original material does.”1

So what is retrieval practice? It is the act of practicing the retrieval of the information you are trying to learn. It is the act of regularly testing yourself, and this is best accomplished using flashcards.

AVOID THE 4 TYPES OF INEFFECTIVE FLASHCARDS

Now, before we jump into the ins and outs of making effective flashcards, we need to clarify what a poorly-made flashcard looks like. This is because almost every student I meet uses flashcards in a way that does not actually lead to effective long-term learning. Let’s discuss the four types of ineffective flashcards:

1. Term-Definition Flashcards

The most common way to use a flashcard is to write a term on the front and its definition on the back. You may be thinking, “What’s wrong with that? I thought that’s how flashcards are supposed to be used?” Well, there are several key reasons why term-definition flashcards don’t make the cut:

- They are most likely not written in your own words. When students make term-definition flashcards, they are usually copying down terms and definitions exactly as they are written in a textbook or in a teacher’s lecture notes as often happens with note taking. Remember, when you are printing, you are not processing.

- They lead to the memorization of words, not the understanding of concepts. When students practice with term-definition flashcards, they are often focusing on regurgitating the definition word-for-word. Memorizing words does not result in true understanding of what something is. True understanding comes from being able to describe a concept in your own words.

- The definition may contain more than one key concept. Sometimes, a single term will have a definition that is 3-4 sentences long. Because regurgitating such a long definition is extremely difficult, most students will only recall part of the definition. Then they will end up reading the definition, which as described previously, rereading is the least effective learning technique. You need to carefully test yourself on every key concept, one at a time.

Due to these and other issues with term-definition flashcards, students will often struggle on an exam and fail to retain information in the long-term. Dr. Kevin J. Pugh makes this clear:

Unfortunately, the first study strategy we tend to learn is rehearsal (repeating some information over and over), and many individuals stick with rehearsal as their go-to study strategy even into adulthood (Ormrod, 2011). In many cases, rehearsal takes the form of memorizing terms and definitions. Students make long lists of terms and definitions or flash cards with terms on one side and definitions on the other. Then they dutifully memorize the terms and definitions. This often works just fine for the test, but not so well for long-term retention.4

2. List Flashcards

The next common type of flashcard you need to avoid are flashcards that have a term on the front and a list of facts about that term on the back. Many of the same issues we already discussed regarding term-definition flashcards apply equally well to list flashcards. The most troublesome aspect of list flashcards is that they test you on more than one concept at a time. Here are 2 major reasons why having more than one fact on the back of a flashcard is a bad idea:

- You are more likely to simply reread the backside of the flashcard. As mentioned with long definitions, you are likely going to have a hard time accurately recalling every bullet point, and due to this difficulty, you may start to simply reread the back of the flashcard without actually recalling the information beforehand.

- You are more likely to “pass off” a flashcard that you didn’t get 100-percent correct. When you recall 3 out of the 4 bullet points correctly, you may tell yourself that you no longer need to review that card because you got it mostly correct. But what if your upcoming exam tests you on that 1 bullet point you got wrong?

As stated by Thomas Frank, “By including multiple facts on one card, you’re more likely to run into illusions of competence.”5 This is because rereading the list on the back of the flashcard leads you to think you know what you can recognize but can’t recall, and when this happens you are more likely to stop reviewing material that you still haven’t memorized yet. Beware of the list flashcard!

3. Class Note Flashcards

As mentioned by UnJaded Jade, “Flashcards should never just be rewritten class notes.”6 There are many problems with this flashcard type, but here are the two major ones:

- Rewriting is not learning. Copying over your notes onto 3×5 cards is called reprinting, which will not result in any kind of deep processing of information. It’s a waste of time.

- Rereading is not learning. Just because you are rereading information that’s on a flashcard doesn’t make it any better than rereading your notes from your notebook.

Durrington Research School summarizes the issues with class note flashcards quite nicely:

Sometimes students will instead write out their notes on to flashcards and end up with a tiny catalogue of summarized notes. The problem here is the flashcard must work the memory, so the action of using them must force the user to dredge information from their long-term memory before checking the answer. If flashcards only contain notes then no retrieval practice will be happening and they might as well re-read their exercise books.7

4. Relying on Friends’ or Unverified Flashcards

You may think that using someone else’s flashcards could be a huge timesaver, which may initially be true since you save the time you would’ve spent making them. BUT, there are several serious issues with using unreliable pre-made flashcards:

- You deprive yourself of the deep learning associated with writing flashcards. Writing a high-quality flashcard requires you to restate what you are learning in your own words, creating a connection between the content and your brain.

- You have a different brain than the person who made the flashcards. Thomas Frank suggests that when you make your own flashcard, you create unique neural pathways for that information. Your neural pathways for a certain concept are different than someone who might share their flashcards with you, so it may take more work to develop those pathways yourself.3

- You will likely miss out on key information not included in the flashcards. Whoever made the flashcards may have skipped out on key information that you need to know for your upcoming exam.

- They might be low quality. You never know what you are going to get when you use someone else’s flashcards, or if they are even correct. They might also fall into the first 3 types of ineffective flashcards too!

THE 6 PROPERTIES OF EFFECTIVE FLASHCARDS

Now that you understand how you shouldn’t make flashcards, let’s talk about how you should. Here are 6 properties of effective flashcards:

1. Questions that Require an Explanation

The most important property of an effective flashcard is that it has a question on the front and an answer on the back. Typically, the best questions are those which require you to describe the answer in your own words: “Are some kinds of retrieval practice more effective for long-term learning than others? Tests that require the learner to supply the answer, like an essay or short-answer test, or simply practice with flashcards, appear to be more effective than simple recognition tests like multiple choice or true/false tests.”1

For instance, you might write a question such as, “What is the purpose of DNA as compared with RNA?” Notice how this question pushes you to describe the concept in your own words. It results in deep engagement with the material.

Almost all the previously mentioned poor learning methods such as rereading fail because they don’t get you to actually think about the material. They are passive activities that require very little, if any, brain power. The more you have to use your brain while reviewing the material, the better. As mentioned in Make It Stick: “Learning is deeper and more durable when it’s effortful. Learning that’s easy is like writing in sand, here today and gone tomorrow.”1

2. Similar to the Upcoming Exam

Whenever I had a test coming up in college, I would plan on spending a few hours the day before the exam reviewing all of my flashcards that related to the material that would be on the test. I’d review the flashcards until I got every single one correct. Having “passed” my flashcard exam, I would stroll into the testing center feeling confident that I would pass the actual exam. My flashcards acted as a warm-up exam.

The reason this worked so well for me, is that as I wrote my flashcards, I’d put myself in the shoes of my professor. As I read the textbook or listened to a lecture, I’d ask myself, “If I were writing the exam, what questions would I ask?” Then I’d write those questions on the front of my flashcards. Essentially, my flashcard stack became my predicted version of the upcoming exam.

Over time, I got better and better at reading the minds of my professors. You start to get a feel for what they think is important based on how they present it. Additionally, the more of their quizzes and tests that you take, the better feel you get for how and what they test.

In the world of sports, they say, “practice like you play and you will play like you practice.” This is your goal when making and reviewing flashcards. If you are in a Spanish class, and you know there will be a portion of the exam involving translating Spanish sentences into English, put Spanish sentences on the front of your flashcards and their English translations on the back of your flashcards. On the other hand, if have to translate English to Spanish, put English on the front of your flashcards. Test yourself exactly like the real test will.

3. Bitesize

Let’s imagine that you are tasked with memorizing what happened during the civil war. If you were to make a flashcard with “What advantages did the North have during the civil war?” on the front, you’d have a hard time answering since there are an infinite number of ways to answer this question, and there will be many individual facts contained on the back of the flashcard. This would result in the same issues we previously discussed regarding list flashcards.

The better thing to do is to break down bigger, multifaceted concepts into bitesize pieces: “Don’t force your brain to remember a complex and wordy answer. It’s easier for your brain to process simpler information so split up your longer questions into smaller, simpler ones. You will end up with more flashcards this way but your learning will be a lot more effective.”5

For instance, we might break up the civil war flashcard into several questions such as “Why did the North have easier access to war materials?”, “Why was the North able to more quickly resupply its armies”, and “Were slaves an advantage or disadvantage to the South? Why?” These questions are easier to process and only have one simple correct answer. This is important because “you should always try to make sure your brain works in the exactly same way at each repetition.”7

4. Connected

In Computers, Cockroaches, and Ecosystems, Dr. Pugh suggests that our brains are very much like search engines with our memories as individual websites. When you search for something on Google, the most prominent websites will be those that are used often and that are linked to from other prominent websites. Similarly, when you rack your brain for an idea, you will be most likely to recall memories that you use often and that are well-connected to other memories.

For this reason, if you want your brain to remember a new concept, you should make a conscious effort to connect it with something you already know, preferably a prominent, important memory. As Kevin Horsely maintains, “all learning is creating a relationship between the known and the unknown.”8

For instance, I’ve recently been making an effort to be better at remembering the names of new people that I meet, and I’ve found the following strategy to be extremely effective. Let’s say I meet someone named Jim. I’d quickly think of someone that I already know named Jim like my Uncle Jim. I’d then make a comparison between the new Jim and my Uncle Jim. How are they similar? They are both tall with brown hair. How are they different? My Uncle is in shape, but this new Jim is overweight. After making these connections between the Jim I already know and this new Jim, I often find that I have a very hard time forgetting the new person’s name. Relating new information to what you already know is so effective that it has it’s own psychological term: “self-referential encoding.” It is often cited as the very most effective memory technique: “One of the most effective ways of enhancing memories is to provide them with a link to your personal life.”5

In addition to self-referential encoding, mnemonic devices can help you make stronger connections: “A mnemonic devices is anything that helps you build an association between two pieces of information in your mind.”5 For instance, let’s say you are trying to remember that Fe is the symbol for Iron. A helpful mnemonic device might be “Villains Fear Ironman.” And as with all aspects of learning, it is best for you to invent your own mnemonic devices rather than copying someone else’s.

5. Written in Your Own Words

As mentioned previously as one of the pitfalls of notetaking and term-definition flashcards, simply rewriting information is not an effective learning method. In fact, in one study, the subjects “scored significantly (approximately half a letter grade) better on the [concepts] they had written about in their own words than on those they had copied.”1

Putting concepts into one’s own words is known as elaboration: “If you’re just engaging in mechanical repetition, it’s true, you quickly hit the limit of what you can keep in mind. However, if you practice elaboration, there’s no known limit to how much you can learn. Elaboration is the process of giving new material meaning by expressing it in your own words and connecting it with what you already know. The more you can explain about the way your new learning relates to your prior knowledge, the stronger your grasp of the new learning will be, and the more connections you create that will help you remember it later.”1

When you use Elaboration, you put concepts into your own words, creating a connection between the new information and your own neural network. If you simply copy down information, this connection will not happen.

6. Includes Pictures and Text

The Picture Superiority Effect suggests that we remember visual information better than written information.8And the effect is astounding: “We are incredible at remembering pictures. Hear a piece of information, and three days later you’ll remember 10% of it. Add a picture and you’ll remember 65%.”8

But, this doesn’t mean you should just use pictures. A recent study proved that including text with a picture enhances memory: “A post-picture sentence improves attention to and perhaps rehearsal of the representation of the picture following its display.”8

For this reason, whenever possible, I’d recommend drawing pictures on your flashcards. And don’t just paste in someone else’s picture off the internet. Drawing your own will enhance your memory of it (even if your art skills are toddler level)

5 STEPS TO WRITING AND REVIEWING FLASHCARDS

Now that you understand what makes a flashcard good vs. bad, let’s quickly discuss the ins and outs of when and how you should write and review them. Here are my 5 steps to writing and reviewing your flashcards:

1. Be Prepared to Write Flashcards During Every Learning Opportunity

If you ran into me while I was at college, chances are I had a stack of flashcards nearby. I used flashcards during every single learning opportunity. Whether I was doing practice problems, reading a textbook, watching an assigned video, or sitting in a lecture, I had a pen and blank flashcards at the ready.

Why? Think about it. Good professors don’t just give you homework to fill up time. They don’t give lectures just for the heck of it. Everything has a purpose, and usually that purpose has something to do with preparing you for the upcoming exam and eventually the final exam. For this reason, I approached every single learning activity with the mindset that I was eventually going to be tested on everything I was currently doing.

This is not what most college students do. Typically, their goal is to simply finish and get a good grade on the assignment at hand. But, that is obviously a nearsighted goal, especially when you consider the fact that homework assignments typically only account for a small fraction of the final grade. It’s important to shift your mindset and view homework assignments and lecture quizzes as learning opportunities that are meant to prepare you for what actually counts, the exams.

So, when I’m doing a homework assignment, and I learn something new, I pause and write a flashcard. Sure, it may take me a little bit longer to get my homework done compared to the average student, but it will save me huge amounts of time when I am reviewing for the exam. While other students are attending long TA review sessions, I’m spending a fraction of the time reviewing my flashcards, feeling confident that I’ve captured every piece of knowledge that the professor wants me to know.

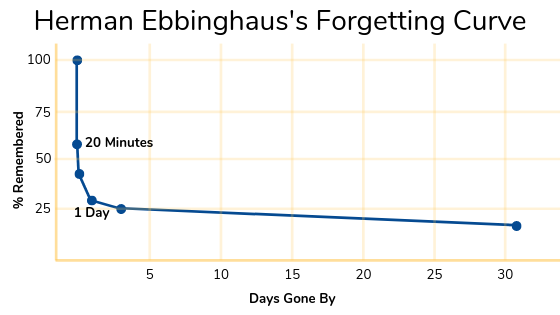

Another thing I want to touch on is that it is important to make flashcards during learning activities, and not after. Some students will write notes during the lecture and then convert their notes into flashcards later. Not only is this time consuming, but it will also decrease your ability to remember what was taught. Why? The answer comes from Herman Ebbinghaus’s Forgetting Curve:

As you can see, just 20 minutes after a lecture, you will likely only remember about 55-percent of what you learned. If you made flashcards during class, however, you’ll be able to test yourself on what you learned while you are walking to your next class. This will interrupt the forgetting curve right away, boosting your retention back up towards 100-percent. This would not be possible if you waited until later to convert your notes into flashcards.

Now, some of you may find it hard to write effective flashcards during a fast-paced lecture, but please don’t let that hold you back. The key is to come to class prepared. When possible, you should read the textbook and make flashcards from it before coming to class. This way, instead of trying to capture everything the professor is saying during class, you only have to capture the information that wasn’t already contained in the textbook. As an example, I typically made 50-100 flashcards based on the textbook reading and then only an additional 10-20 during each class.

For the MCAT specifically, there’s a few opportunities you have to pause and create your own flashcards. As you go through our free Ecourse, you can pause during the videos or the associated content review book reading to write high-quality flashcards on concepts you aren’t sure you will remember on test day. You can also pause as you go through our over 5,300 Quizlet flashcards associated with our Ecourse and write your own flashcards based on topics you missed on our flashcards.

Now, how does using MCAT Self Prep’s flashcards work with the rest of the advice given here? Written in 2017 and updated weekly with any feedback we receive, we know that these flashcards are high-quality and comprehensive. We have images associated with most flashcards too, capitalizing on the Picture Superiority Effect. These are connected, bitesize, and require explanations to fully understand. And when you come across flashcards you struggle with or can’t easily explain, that’s your opportunity to create a flashcard in your own words and start establishing those neural connections!

Additionally, to write flashcards faster, I’d recommend developing shorthands, and when these are visual, all the better. For instance, up and down arrows can indicate increases and decreases. Or, you could replace long terms like “Restriction Endonuclease” with its abbreviation, RE. This way, your brain has to work harder to replace the term, resulting in deeper learning.6

2. Gain Understanding Before Writing Flashcards

So, during a learning opportunity, how should you go about writing flashcards? Well, before you write a flashcard, it is crucial that you first understand what is being taught. After all, how can you possibly write a question to test yourself on a concept that you don’t yet understand. As Dr. Wozniak explains, “Do not start from memorizing loosely related facts! First read a chapter in your book that puts them together (e.g. the principles of the internal combustion engine). Only then proceed with learning using individual questions and answers (e.g. What moves the pistons in the internal combustion engine?)”4

Now, what if you don’t understand a certain paragraph in the textbook? Something I’ve found effective, is to keep a running list of questions to ask the professor during the next lecture. For the MCAT specifically, you can go to one of our tutors (who all scored in the 97th percentile or better on the MCAT) to ask your questions!

It is crucial to be 100-percent honest with yourself. It’s okay to not understand something, but don’t just skip over it. Put in the necessary work to figure it out.

3. Capture Every Concept You Expect to be Tested On

This leads me into my next point. Don’t skip anything! Try your best to make a flashcard for every single concept from every textbook chapter, every video, every practice assignment, and every lecture. Even if it seems simple, don’t let it pass by:

Do not neglect the basics. Memorizing seemingly obvious things is not a waste of time! Basics may also appear volatile and the cost of memorizing easy things is little. Better err on the safe side. Remember that usually you spend 50% of your time repeating just 3-5% of the learned material! Basics are usually easy to retain and take a tiny proportion of your time. However, each memory lapse on a basic fact can be very costly!4

4. Do a Practice Session as Soon as Possible

As mentioned before, you will forget almost 50-percent of what you learned just 20 minutes later. For this reason, it is crucial to review the flashcards you made right after class. Additionally, when I am reading a textbook, I try to pause every 30 minutes or so to review the flashcards I made during the previous half-an-hour.

Research consistently shows an immediate practice session to be worth the time investment:

Students heard a story that named sixty concrete objects. Those students who were tested immediately after exposure recalled 53 percent of the objects on this initial test but only 39 percent a week later. On the other hand, a group of students who learned the same material but were not tested at all until a week later recalled 28 percent. Thus, taking a single test boosted performance by 11 percent after a week.1

An immediate practice session and the subsequent 11-percent boost on a test could be the difference between earning a C+ and an A-. It’s the little things that make all the difference.

5. Have Practice Sessions at Increasingly Spaced Out Intervals

As you can probably guess, three practice sessions is better than one. In continuation of the research recently cited:

Another group of students were tested three times after initial exposure and a week later they were able to recall 53 percent of the objects—the same as on the initial test for the group receiving one test. In effect, the group that received three tests had been “immunized” against forgetting, compared to the one-test group, and the one-test group remembered more than those who had received no test immediately following exposure. Thus, and in agreement with later research, multiple sessions of retrieval practice are generally better than one, especially if the test sessions are spaced out.1

As you can see, it is important to practice your flashcards several times, but how should these practice sessions be spaced out? I think this answer from Make It Stick sums it up quite nicely:

How big an interval, you ask? The simple answer: enough so that practice doesn’t become a mindless repetition. At a minimum, enough time so that a little forgetting has set in. A little forgetting between practice sessions can be a good thing, if it leads to more effort in practice, but you do not want so much forgetting that retrieval essentially involves relearning the material. The time periods between sessions of practice let memories consolidate. Sleep seems to play a large role in memory consolidation, so practice with at least a day in between sessions is good.1

During college, I found that the following intervals worked very well for me:

- Review my flashcard stack immediately after the learning activity

- Review all my flashcard stacks the day after making them

- Review all my relevant flashcard stacks the day before the exam

- Review all my flashcard stacks the day before the final exam

You may find that you need more practice sessions than this, and that is okay. You may be fine with less. You have to find the balance that works for you.

The key here is to spread out your review sessions instead of cramming the night before the exam. Instead of staying up into the late hours of the night studying for an exam, I typically get all my review sessions in just walking around campus. As suggested by Zane Claes, “The best way to use flashcards is as a quick impromptu study session. 15 minutes at the bus stop and 30 minutes between classes is better than hours and hours of continuous study at the end of the day.”6

TIPS FOR EFFECTIVE PRACTICE SESSIONS

Making effective flashcards is just half the battle, you also need to make sure your practice sessions are as effective as possible. Here are 5 key tips for having the most effective practice sessions possible:

1. Treat it Like an Exam. Don’t Just Read Your Flashcards

Remember, “practice like you play and you will play like you practice.” For this reason, you need to treat your practice sessions like the real deal. That means you need to be honest and hold yourself accountable. You should attempt to answer the question without peeking at the back, and if you get it wrong, you need to mark it wrong for future review.

“Evidence tells us that the act of trying to remember, even if unsuccessful, aids learning. Therefore a proper pause is a must before flipping the card.”7

2. Say Your Answers Out Loud While Studying

In holding yourself accountable, it can be helpful to answer the question out loud. This forces you to pause before flipping over the card. It also forces you to articulate a clear answer that is either right or wrong.

Answering out loud also helps with elaboration (putting concepts into your own words). It will greatly enhance your understanding if you imagine you are teaching the concept to a fifth grader. As Einstein say, “The definition of genius is taking the complex and making it simple.”

3. Review the Flashcards You Got Wrong Immediately After Every Practice Session

One of my favorite sayings is “Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.” That couldn’t be more true when it comes to practicing your flashcards. When you get a flashcard incorrect, you are practicing it wrong. Therefore, you need to practice it until your most recent repetition of it is perfect.

Practice doesn’t make perfect. Perfect practice makes perfect.

For this reason, when you get a flashcard wrong, I strongly recommend flipping it upside down or marking it in some way. Then after you finish going through the flashcard stack, you should retest yourself on the marked cards until you get them all 100-percent correct.

4. Switch Between Different Subjects Often (Interleaving)

A large body of research suggests that students who study a variety of subjects throughout the day will perform better than students who only study a single topic. Switching between subjects is known as interleaving.

As an example, in college, when I’d plan out my week, I’d try and study a variety of subjects each day. Instead of doing all my Biology homework on Monday, all of my Physics homework on Tuesday, and all of my English homework on Wednesday, etc. etc., I’d do an hour or two of homework from each subject every day. Not only does this help you stay engaged, but it also enhances your memory of what you are learning.

5. Mix Up the Order of Your Questions (Varied Practice)

While interleaving entails switching between different subjects, varied practice entails mixing up concepts within the same subject. It is also proven to be an effective method for boosting memory retention.

For instance, let’s say you’ve written four questions that require the use of four different physics questions. If you were to study these questions in the same order every time, you may start to remember that question #1 uses equation A, question #2 uses equation B, and so on and so forth. This aides your memory in a way that is not realistic to the randomized conditions of your upcoming exam. What you should do is mix up the order of these questions so that you actually have to remember which equation is needed in which scenario.

Because I prefer to keep my flashcards organized, I avoid mixing them up willy nilly, but I do try to randomize the order of certain subsets of questions when I think it might make my practice more effective. For our MCAT Self Prep flashcards, we recommend using the shuffle function within any given lesson, so the notecards are still organized by topic, but in a random order within that topic.

CONCLUSION: LEARNING IS DEEPER WHEN IT IS MORE EFFORTFUL

If you made it to the end of this article, you are likely thinking to yourself, “Holy cow! Flashcarding like this sounds like so much work!” And you would be right. It isn’t easy. But, the fact that flashcarding like this is so hard is the very same reason why it is so effective: “Learning is deeper and more durable when it’s effortful. Learning that’s easy is like writing in sand, here today and gone tomorrow.”1 If you want to actually remember what you are learning, I’d highly recommend adopting this method of studying. You won’t regret it!

If you want to watch me make high-quality flashcards specifically for the MCAT, watch my Free Intro Session. I cover 12 more tips for making effective flashcards and explain the most important strategies for working your way towards a top MCAT score.

Warm regards,

Andrew George

For more MCAT Tips:

Sign up for our affordable elite MCAT tutoring.

Sign up for our FREE MCAT Prep Course.

Follow us on:

Sources

- Make It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, and Mark A. McDaniel.

- “Study Trap: ‘Illusions of Competence,’ Or When You Actually Don’t Know What You Think You Know by Memory Improvement Tips”

- “Re-reading Is Ineffective. Do This Instead.” by Jonathan Vieker

- Computers, Cockroaches, and Ecosystems by Kevin J. Pugh

- “Effective Flashcards” by Durrington Research School

- “How to Study Effectively with Flash Cards” by Thomas Frank

- “5 Tips for Powerful Flashcards and Better Exam Revision” by Chloe Burroughs

- “Effective Learning: Twenty Rules of Formulating Knowledge” by Dr. Piotr Wozniak

- Unlimited Memory by Kevin Horsley

- “Picture Superiority Effect” by Wikipedia

- “Vision Trumps all Other Senses” by John Medina

- “Picture Recognition Improves With Subsequent Verbal Information” by Journal of Experimental Psychology Learning Memory and Cognition